Tuesday, April 2, 2013

Thailand extends free bus & train services

BANGKOK, 1 April 2013

The cabinet has decided to extend free bus and train services for six more months, while the transport minister has proposed an idea of a free public transport ticket for low-income people.

At the mobile cabinet meeting in Chachoengsao province, the cabinet has approved an extension of the government's free bus and train services for another six months.

The free services currently include non-air-conditioned buses in Bangkok on 73 routes, and third-class train services on about 170 trains per day. The service extension is expected to cost the government 2 billion baht.

Meanwhile, Transport Minister Chadchart Sittipunt proposed at the cabinet meeting the idea of a free ticket for low-income people, to be used on all public transport services. The idea would be further discussed in future meetings, and no decision has been made on the idea yet.

NNT - National News Bureau of Thailand

Thursday, March 28, 2013

NZ Herald: All day congestion tipped for Auckland

Even the inter-peak period of 9am to 3pm is in line for a dramatic increase in congestion.

Photo: Sarah Ivey

By Mathew Dearnaley

NZ Herald Thursday Mar 28, 2013

A new report from Auckland Transport predicts significantly worsening congestion between morning and afternoon traffic peaks after 2021 under existing budgets providing $34 billion of transport funding over the next 30 years.

Even if that can be boosted to $59 billion to pay for all desired projects with extra revenue, such as from road tolls or higher parking levies - also serving to reduce travel demand - it warns that its programme will not keep ahead of traffic growth in the second and third decades of the planning horizon.

The budget compares with $7 billion spent on transport around Auckland since 2000.

About two-thirds of the desired $59 billion would be to pay for new and existing roads compared with $19 billion for public transport and $760 million for walking and cycling facilities.

Not only will drivers face ever-lengthening morning traffic queues, but those trying to get about the region in what is called the inter-peak period of 9am to 3pm are in line for a dramatic increase in congestion from about 2023 under the "committed" $34 billion funding scenario, says the report.

It says that by then, 25 per cent of all road travel between 7am and 3pm across Auckland will be in excessive congestion, compared with about 12 per cent during morning peaks now, and 5 per cent in the inter-peak. It does not include data about evening travel, but that is unlikely to be much better, if any.

The report says that although some congestion must be expected in "a thriving, successful city of two million people", levels forecast for Auckland by 2041 are well above those now experienced in centres such as Sydney and Melbourne with their already considerably larger populations.

Even under a "fully-funded" programme, the report fears inter-peak congestion will start overtaking morning delays by about 2038.

It says that although better public transport can relieve pressure on roads for trips to and from work, it is less able to help between times.

But it believes a planned extension of higher frequency bus routes over the next three years - operating from 7am to 7pm every day of the week - should make some difference.

Both the Campaign for Better Transport and city council transport chairman Mike Lee have been urging Auckland Transport to also increase inter-peak and weekend trains to stem a decline in rail patronage.

Transport commentator Matt Lowrie is questioning the validity of the modelling behind the report, noting on a blog site hosted by the campaign that there is nowhere else in the world where roads are busier between morning and afternoon commuter runs.

He is "embarrassed" that even supposing alternative transport schemes can be fully funded to reduce reliance on cars, the report predicts a 17 per cent rise in Auckland's carbon dioxide emissions by 2041, against a target reduction of 49 per cent.

THE NUMBERS:

• $60b Desired transport funding to 2041• $34b What has been committed so far from available sources

• $45b- $50b Expected funding before resorting to new sources such as tolls or higher parking levies to reduce road travel demand

• $7b Transport spending in Auckland since 2000

Fare-free transit spreading in Europe?

By Jarrett Walker from his blogsite: humantransit.org

Jarrett visited Auckland last week to offer advice on public transport

It's too soon to say, but Tallinn, Estonia

(pop. 425,000) is now by far the largest city to offer fare-freefree

public transit -- not just in Europe but anywhere in the world as near

as I can tell. Most other free-transit communities are either

university-dominated small cities (like Chapel Hill, North Carolina and

Hasselt, Belgium) or rural networks where ridership is so low that fares

don't pay for the costs of fare collection technology, let alone

contribute toward operating cost.

Tallinn -- along with Hasselt and the small city of Aubagne, France -- are also forming the Free Public Transport European Network, to spread the idea and disseminate experience about it.

As the city's webpage explains, Tallinn citizens must still buy a farecard, which will allow them to ride free. This allows the transit network to continue to collect fares from tourists and people living in other cities.

This raises the interesting possibility that any city, inside a bigger metro area with a regional transit system, could elect to subsidize transit fares for its own residents, by simply buying fares in bulk and giving them away to its own residents -- just as some universities and employers already do for their own students or staff. Indeed, smart farecards make it possible for anyone to subsidize fares without much complexity, opening up a huge range of subsidy possibilities for any entity that sees an advantage in doing so. Yet another reason that city governments are not as helpless about transit as they often think, even if they don't control their transit system.

Tallinn -- along with Hasselt and the small city of Aubagne, France -- are also forming the Free Public Transport European Network, to spread the idea and disseminate experience about it.

As the city's webpage explains, Tallinn citizens must still buy a farecard, which will allow them to ride free. This allows the transit network to continue to collect fares from tourists and people living in other cities.

This raises the interesting possibility that any city, inside a bigger metro area with a regional transit system, could elect to subsidize transit fares for its own residents, by simply buying fares in bulk and giving them away to its own residents -- just as some universities and employers already do for their own students or staff. Indeed, smart farecards make it possible for anyone to subsidize fares without much complexity, opening up a huge range of subsidy possibilities for any entity that sees an advantage in doing so. Yet another reason that city governments are not as helpless about transit as they often think, even if they don't control their transit system.

Global warming predictions prove accurate

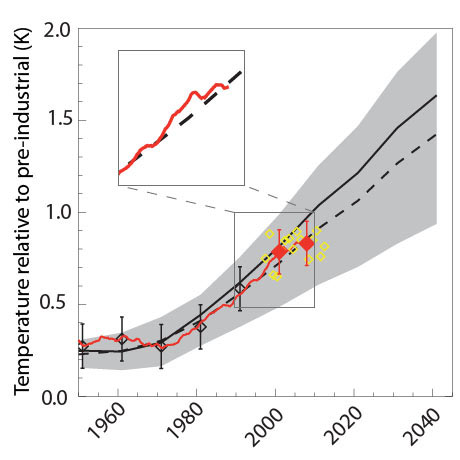

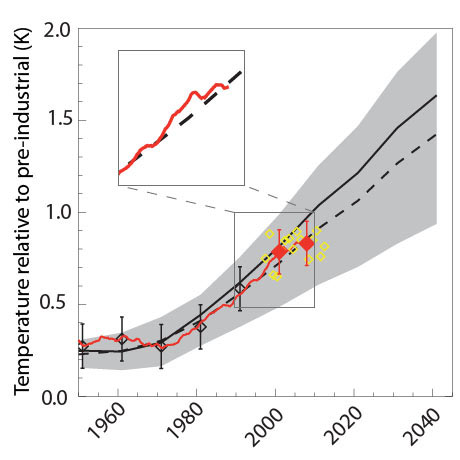

Forecasts of global temperature rises over the past 15 years

have proved remarkably accurate, new analysis of scientists' modelling

of climate change shows.

The debate around the accuracy of climate modelling and forecasting has been especially intense recently, due to suggestions that forecasts have exaggerated the warming observed so far – and therefore also the level warming that can be expected in the future. But the new research casts serious doubts on these claims, and should give a boost to confidence in scientific predictions of climate change.

The paper, published on Wednesday in the journal Nature Geoscience, explores the performance of a climate forecast based on data up to 1996 by comparing it with the actual temperatures observed since. The results show that scientists accurately predicted the warming experienced in the past decade, relative to the decade to 1996, to within a few hundredths of a degree.

The forecast, published in 1999 by Myles Allen and colleagues at Oxford University, was one of the first to combine complex computer simulations of the climate system with adjustments based on historical observations to produce both a most likely global mean warming and a range of uncertainty. It predicted that the decade ending in December 2012 would be a quarter of degree warmer than the decade ending in August 1996 – and this proved almost precisely correct.

The study is the first of its kind because reviewing a climate forecast meaningfully requires at least 15 years of observations to compare against. Assessments based on shorter periods are prone to being misleading due to natural short-term variability in the climate.

The debate around the accuracy of climate modelling and forecasting has been especially intense recently, due to suggestions that forecasts have exaggerated the warming observed so far – and therefore also the level warming that can be expected in the future. But the new research casts serious doubts on these claims, and should give a boost to confidence in scientific predictions of climate change.

The paper, published on Wednesday in the journal Nature Geoscience, explores the performance of a climate forecast based on data up to 1996 by comparing it with the actual temperatures observed since. The results show that scientists accurately predicted the warming experienced in the past decade, relative to the decade to 1996, to within a few hundredths of a degree.

The forecast, published in 1999 by Myles Allen and colleagues at Oxford University, was one of the first to combine complex computer simulations of the climate system with adjustments based on historical observations to produce both a most likely global mean warming and a range of uncertainty. It predicted that the decade ending in December 2012 would be a quarter of degree warmer than the decade ending in August 1996 – and this proved almost precisely correct.

The study is the first of its kind because reviewing a climate forecast meaningfully requires at least 15 years of observations to compare against. Assessments based on shorter periods are prone to being misleading due to natural short-term variability in the climate.

The climate forecast published in 1999 is showed by the dashed black

line. Actual temperatures are shown by the red line (as a 10-year mean)

and yellow diamonds (for individual years). The graph shows that

temperatures rose somewhat faster than predicted in the early 2000s

before returning to the forecasted trend in the last few years. [Graph: Nature Geoscience]

The new research also found that, compared to the forecast, the early

years of the new millennium were somewhat warmer than expected. More

recently the temperature has matched the level forecasted very closely,

but the relative slow-down in warming since the early years of the early

2000s has caused many commentators to assume that warming is now less

severe than predicted. The paper shows this is not true.

Allen said: "I think it's interesting because so many people think that recent years have been unexpectedly cool. In fact, what we found was that a few years around the turn of the millennium were slightly warmer than forecast, and that temperatures have now reverted to what we were predicting back in the 1990s."

He added: "Of course, we should expect fluctuations around the overall warming trend in global mean temperatures (and even more so in British weather!), but the success of these early forecasts suggests the basic understanding of human-induced climate change on which they were based is supported by subsequent observations."

Allen said: "I think it's interesting because so many people think that recent years have been unexpectedly cool. In fact, what we found was that a few years around the turn of the millennium were slightly warmer than forecast, and that temperatures have now reverted to what we were predicting back in the 1990s."

He added: "Of course, we should expect fluctuations around the overall warming trend in global mean temperatures (and even more so in British weather!), but the success of these early forecasts suggests the basic understanding of human-induced climate change on which they were based is supported by subsequent observations."

Sunday, March 24, 2013

Free public transport: from social experiment to political alternative?

by Maxime Huré

& translated by

Oliver Waine, 20/03/2013

Mots-clés : public space

| public transportation

| market

| mobility

| transport

| public policy

| free

All the versions of this article:

[English]

[français]

In a work combining storytelling and reflection, a local councillor and a philosopher analyse the policy of free public transport implemented since 2009 in Aubagne, near Marseille.

A resounding success with residents, this experiment has opened the way to a stimulating debate on the feasibility of policies that offer an alternative to market-led solutions in urban areas.

Reviewed : Giovannangeli, M. and Sagot-Duvauroux, J.‑L. 2012. Voyageurs sans ticket. Liberté, égalité, gratuité : une expérience sociale à Aubagne, Vauvert: Au Diable Vauvert.

Free public transport appears to

be something of a taboo subject both in society at large and in the

world of the social sciences. [1]

And yet some 20 urban areas in France have bitten the bullet and gone

down this controversial path in recent years. The scintillating work Voyageurs sans ticket. Liberté, égalité, gratuité : une expérience sociale à Aubagne

(“Passengers without tickets. Liberty, equality, charge-free: a social

experiment in Aubagne”) analyses one such experiment conducted in

Aubagne, a medium-sized town to the east of Marseille, and shows that

this apparent silence on the subject masks a certain timidity on the

part of decision-makers, researchers and citizens, to a large extent

linked to an inability to “think outside the box”. Its two authors –

Magali Giovannangeli, a communist local councillor in Aubagne, and

philosopher Jean‑Louis Sagot‑Duvauroux – offer a rigorous analysis of

free public transport that ultimately becomes a work of political

advocacy. In Aubagne, it would seem that free public transport has led

to a greater involvement of residents in local politics, as well as a

new sense of freedom, while at the same time offering a real alternative

to market forces. This work combines carefully argued analysis with a

clear stance on the public debate, and as such comes across as a

successful collaboration between a researcher and an elected

representative.

But, above all, it is the analysis of the effects on the population that should convince the reader of the merits of this measure. The removal of social barriers, the soothing of tensions, greater recognition for the work of bus drivers, and the end of ticket inspections are all changes that have transformed users’ relationship with transport. According to the authors, buses in Aubagne have – like footpaths and other places where access is free of charge – now become “public spaces” in the broadest sense of the term that have been appropriated by “new citizens of public transport” (p. 120). The hypothesis proposed, inspired by the thinking of philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville (1981), is that the charge-free provision of a service is a vector of freedom. In this regard, the second chapter of the book – which places this hypothesis in a historical context – is particularly enlightening: for example, schools, libraries and public spaces are all free, and each of these places provides individuals with a form of freedom.

Is social appropriation the key to the scheme’s success? This hypothesis, put forward by the authors, can be discussed in the light of recent studies concerning innovative mobility policies. For instance, social appropriation was undoubtedly a factor in the success of France’s first self-service bicycle-hire experiment, in La Rochelle in 1976 (Huré 2012). In Aubagne, think tanks were organised at the initiative of citizens or set up by the Communauté d’Agglomération du Pays d’Aubagne et de l’Étoile (the intermunicipal council covering the 12 towns and villages in the Aubagne urban area) to promote and complement new practices among users. In addition to reclaiming public space in this way, free public transport is also seen as a means of involving citizens in the political process, by helping them to “become aware” that transport policy is one of the major political issues of the 21st century (pp. 124–126). Finally, in the authors’ view, free public transport is something that “goes against current trends and represents a clear alternative to the market-based approach” (p. 35).

These reflections allow us to question contemporary ideological shifts, at a time when current debates all seem to converge on the word “crisis”, particularly in the field of political thinking. Although not cited, Ivan Illich’s theories on conviviality (Illich 1973a) and the counterproductivity of industrialised transport systems (Illich 1973b) – the very foundations of political ecology – are brought up to date here: if one’s aim is to reduce the role of the car, it is necessary to put in place tools that incentivise rather than restrict, and which create spaces of freedom and conviviality (pp. 138–143). This book can therefore also be read as a work that advocates a transformation of the Left in France, and which promotes political alternatives rather than an alternation of political parties. [3] However, it is also clearly a means of diffusing knowledge about this experiment in France, as Aubagne wishes to play a leading role within the network of towns that have implemented free public transport, while awaiting the adoption of this measure by a European capital (Tallinn in 2013).

Is it therefore possible that free public transport could, on the contrary, reinforce the market by giving a new legitimacy and a positive image to urban-services firms? This also raises serious questions about the degree to which of public institutions can organise the market (Hall and Soskice 2001), particularly in terms of the service offer proposed. Accordingly, the authors believe that free public transport is a means of opposing the integrated fare policies [5] of large urban areas. Aubagne, for instance, forms part of the Marseille urban area geographically, [6] but has to date refused to join the city’s intermunicipal council, the Marseille Provence Métropole (MPM) urban community, instead preferring to create its own intermunicipal structure (the Communauté d’Agglomération du Pays d’Aubagne et de l’Étoile, CAPAE). With this in mind, the partnership with Veolia represents an additional, non-negligible resource in Aubagne’s efforts to remain independent from Marseille; indeed, MPM does not look upon Aubagne’s experiment kindly, as it prevents fare harmonisation across the metropolitan area, unless Marseille’s network were also to be made free of charge.

In addition, the agreement between the CAPAE and its public transport providers was attacked by the prefect of the Bouches-du-Rhône département (in which Marseille and Aubagne are located) on technical grounds relating to the compensation of transport companies in the context of a public-service delegation. According to the authors, this procedure was highly political in nature, representing the culmination of a clash between the French state, represented at the time by Nicolas Sarkozy, and a left-wing municipality (chapter 5: “Aubagne vs Sarko”, pp. 81–96). Nevertheless, this resistance to integrated fares may also be seen as part of a fight to prevent the growth of private monopolies across ever larger areas. In the Paris region, the implementation of a flat-rate fare system, [7] managed by private operators, has preceded the creation of a Greater Paris authority. As a result, certain authors have talked about “back-to-front intermunicipality” (Baraud-Serfaty 2011), as the construction of the market is taking place before the construction of political institutions.

It is clear, therefore, that the choice between free public transport and integrated fare systems has very real political implications. The difference between these two competing measures concerns the way local-government areas and powers are organised, in a context of ongoing discussion and debate on the role of city regions in France. As we have seen, this means that free public transport can become an instrument of resistance wielded by medium-sized towns in the face of attempts at political and territorial domination by larger urban areas. By implementing an integrated fare system, these big cities use economic stakeholders to organise their territories and political powers. Why couldn’t Aubagne do the same with free public transport? In the field of the social sciences, “thinking alternative” means opening up new perspectives in order to understand the organisation of our contemporary societies, [8] a stimulating account of which is proffered here in Voyageurs sans ticket.

Bibliographie

A social experiment in transforming “public space”

The analysis of the experiment is based first of all on figures, in response to the economic arguments of the many “hostile opponents” (p. 26) to such measures: the implementation of free public transport on the 11 bus routes [2] that serve the 100,000 inhabitants of the Aubagne urban area has resulted in a 142% increase in ridership across the network between 2009 and 2012, a 10% reduction in car journeys over the same period, a service satisfaction rating of 99%, a drop in public expenditure per journey from €3.93 in 2008 to €2.04 in 2011 – and all without any increase in taxes for local residents. Presented like this, free public transport appears to be an effective response to the problems of passenger transport and pollution due to exhaust fumes.But, above all, it is the analysis of the effects on the population that should convince the reader of the merits of this measure. The removal of social barriers, the soothing of tensions, greater recognition for the work of bus drivers, and the end of ticket inspections are all changes that have transformed users’ relationship with transport. According to the authors, buses in Aubagne have – like footpaths and other places where access is free of charge – now become “public spaces” in the broadest sense of the term that have been appropriated by “new citizens of public transport” (p. 120). The hypothesis proposed, inspired by the thinking of philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville (1981), is that the charge-free provision of a service is a vector of freedom. In this regard, the second chapter of the book – which places this hypothesis in a historical context – is particularly enlightening: for example, schools, libraries and public spaces are all free, and each of these places provides individuals with a form of freedom.

Is social appropriation the key to the scheme’s success? This hypothesis, put forward by the authors, can be discussed in the light of recent studies concerning innovative mobility policies. For instance, social appropriation was undoubtedly a factor in the success of France’s first self-service bicycle-hire experiment, in La Rochelle in 1976 (Huré 2012). In Aubagne, think tanks were organised at the initiative of citizens or set up by the Communauté d’Agglomération du Pays d’Aubagne et de l’Étoile (the intermunicipal council covering the 12 towns and villages in the Aubagne urban area) to promote and complement new practices among users. In addition to reclaiming public space in this way, free public transport is also seen as a means of involving citizens in the political process, by helping them to “become aware” that transport policy is one of the major political issues of the 21st century (pp. 124–126). Finally, in the authors’ view, free public transport is something that “goes against current trends and represents a clear alternative to the market-based approach” (p. 35).

Free transport as a political alternative

The alternative to the market proposed by the authors is first and foremost a political alternative. “Why does free public transport and, more generally, alternative proposals to liberalism occupy such a small space and have such poor visibility in left-wing manifestos?” (p. 208) asks communist councillor Magali Giovannangeli, who, in the course of this experiment, also begins to question her political identity. In particular, she condemns the ideological inflexibility of the traditional political parties, who prefer to regulate the price of public transport using concessionary fares rather than promote free public transport. In this introspective section of the book, both the councillor and the philosopher – who handed in his Communist Party card over 20 years ago – seem to effect an ideological shift and harness the ideas of the degrowth movement (Mouvement de la Décroissance; p. 142). Furthermore, the authors make no secret of the fact that the title of their book is borrowed from Liberté, égalité, gratuité by Paul Ariès (2011), a key intellectual figure in this movement.These reflections allow us to question contemporary ideological shifts, at a time when current debates all seem to converge on the word “crisis”, particularly in the field of political thinking. Although not cited, Ivan Illich’s theories on conviviality (Illich 1973a) and the counterproductivity of industrialised transport systems (Illich 1973b) – the very foundations of political ecology – are brought up to date here: if one’s aim is to reduce the role of the car, it is necessary to put in place tools that incentivise rather than restrict, and which create spaces of freedom and conviviality (pp. 138–143). This book can therefore also be read as a work that advocates a transformation of the Left in France, and which promotes political alternatives rather than an alternation of political parties. [3] However, it is also clearly a means of diffusing knowledge about this experiment in France, as Aubagne wishes to play a leading role within the network of towns that have implemented free public transport, while awaiting the adoption of this measure by a European capital (Tallinn in 2013).

A true fight against market forces?

Does making public transport free of charge really weaken the influence of market forces? Although it attacks a fundamental value of capitalism – commercial exchanges – the experiment is still organised within the context of the market economy. As the authors concede, “a company that has the necessary equipment and know-how, and which provides an essential service to the population, cannot simply be replaced” (p. 69); and, indeed, Veolia is still the transport operator in Aubagne. Moreover, the public funding of free public transport is provided by an increase in the versement transport (transport contribution) [4] levied on businesses, a move which is not possible in all urban areas, in particular those that have already reached their upper taxation limits. Finally, although ticketing costs have been eliminated, investments to improve clock-face scheduling have generated a 20% increase in overall costs. During negotiations, Veolia also succeeded in imposing a passenger-counting system, recovering €0.40 per passenger as an incentive bonus.Is it therefore possible that free public transport could, on the contrary, reinforce the market by giving a new legitimacy and a positive image to urban-services firms? This also raises serious questions about the degree to which of public institutions can organise the market (Hall and Soskice 2001), particularly in terms of the service offer proposed. Accordingly, the authors believe that free public transport is a means of opposing the integrated fare policies [5] of large urban areas. Aubagne, for instance, forms part of the Marseille urban area geographically, [6] but has to date refused to join the city’s intermunicipal council, the Marseille Provence Métropole (MPM) urban community, instead preferring to create its own intermunicipal structure (the Communauté d’Agglomération du Pays d’Aubagne et de l’Étoile, CAPAE). With this in mind, the partnership with Veolia represents an additional, non-negligible resource in Aubagne’s efforts to remain independent from Marseille; indeed, MPM does not look upon Aubagne’s experiment kindly, as it prevents fare harmonisation across the metropolitan area, unless Marseille’s network were also to be made free of charge.

In addition, the agreement between the CAPAE and its public transport providers was attacked by the prefect of the Bouches-du-Rhône département (in which Marseille and Aubagne are located) on technical grounds relating to the compensation of transport companies in the context of a public-service delegation. According to the authors, this procedure was highly political in nature, representing the culmination of a clash between the French state, represented at the time by Nicolas Sarkozy, and a left-wing municipality (chapter 5: “Aubagne vs Sarko”, pp. 81–96). Nevertheless, this resistance to integrated fares may also be seen as part of a fight to prevent the growth of private monopolies across ever larger areas. In the Paris region, the implementation of a flat-rate fare system, [7] managed by private operators, has preceded the creation of a Greater Paris authority. As a result, certain authors have talked about “back-to-front intermunicipality” (Baraud-Serfaty 2011), as the construction of the market is taking place before the construction of political institutions.

It is clear, therefore, that the choice between free public transport and integrated fare systems has very real political implications. The difference between these two competing measures concerns the way local-government areas and powers are organised, in a context of ongoing discussion and debate on the role of city regions in France. As we have seen, this means that free public transport can become an instrument of resistance wielded by medium-sized towns in the face of attempts at political and territorial domination by larger urban areas. By implementing an integrated fare system, these big cities use economic stakeholders to organise their territories and political powers. Why couldn’t Aubagne do the same with free public transport? In the field of the social sciences, “thinking alternative” means opening up new perspectives in order to understand the organisation of our contemporary societies, [8] a stimulating account of which is proffered here in Voyageurs sans ticket.

Bibliographie

- Ariès, P. 2011. Liberté, égalité, gratuité : pour la gratuité des services publics !, Villeurbanne: Golias.

- Baraud-Serfaty, I. 2011. “La nouvelle privatisation des villes”, Esprit, nos. 3–4, pp. 149–167.

- CERTU. 2010. “Le débat : la gratuité des transports collectifs urbains ?”, Transflash, no. 352, April, pp. 1–3.

- GART. 2012. Une décennie de tarification dans les réseaux de transport urbain.

- Hall, P. and Soskice, D. (eds.). 2001. Varieties of Capitalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Huré, M. 2012. “De Vélib’ à Autolib’. Les grands groupes privés, nouveaux acteurs des politiques de mobilité urbaine”, Métropolitiques, 6 January (also available in English).

- Illich, I. 1973a. La Convivialité, Paris: Le Seuil.

- Illich, I. 1973b. Énergie et équité, Paris: Le Seuil.

- Tocqueville, A. de. 1981 (1st ed. 1835). De la démocratie en Amérique, vol. 1, Paris: Flammarion.

Further reading

- GART. 2012. Une décennie de tarification dans les réseaux de transport urbain (in French): http://www.gart.org/Les-dossiers/Ta....

- CERTU. 2010. « Le débat : la gratuité des transports collectifs urbains ? », Transflash, n° 352, April, pp. 1–3 (in French): http://www.adtc-grenoble.org/IMG/pd....

Footnotes

[1] No scientific research has been conducted on this subject; we may, however, cite the study published by GART (Groupement des Autorités Responsables de Transport, the association of French transport authorities) (GART 2012) and the publication of a debate on free urban public transport in Transflash, the newsletter of CERTU (Centre d’Études sur les Réseaux, les Transports, l’Urbanisme et les Constructions Publiques – Centre for the Study of Urban Planning, Transport and Public Facilities), no. 352 (CERTU 2010). For this issue of Transflash, a number of researchers, elected representatives and professionals expressed their opinions on the matter.[2] In 2014, the network will be complemented by a tram line. A second tram line is also planned for 2019.

[3] It should be noted that the first town to implement free public transport was Compiègne, in 1975, led by a right-wing mayor at the time.

[4] The versement transport (VT) is calculated on the basis of the payroll of companies with more than nine employees. The aim of this tax is to finance urban public transport. The rate at which it is set essentially depends on the size of the urban area and the infrastructures in question. In Aubagne, the VT has increased from 0.6% to 1.8%, in particular to fund the new tram line, which will be the first free light-rail service in the world.

[5] The term “integrated fare system” refers to different fare and ticketing practices that enable users to travel across an entire (intermunicipal) urban transport network, on all available transport modes, using single or combined travel documents that can be purchased at preferential rates.

[6] According to the French statistics office (Insee), Aubagne forms part of the unité urbaine (continuously built-up urban area) of Marseille–Aix‑en‑Provence.

[7] It was planned that, from 2013, all holders of Navigo travel cards, regardless of place of residence or type of travel card, would be able to travel anywhere in the Paris region by bus, tram, metro or suburban rail (RER and Transilien) for the same price. At present, this policy applies only at weekends, when the network is “dezoned”.

[8] This is the aim of the new “Altervilles” master’s programme that has been offered since September 2012 by Sciences Po Lyon and the Université Jean Monnet in Saint-Étienne: http://altervilles.universite-lyon.fr.

From MetroPolitics.eu 20/3/2013.

Friday, March 22, 2013

Monday, March 18, 2013

No evidence Wellington flyover will ease traffic congestion

Facts don't support expressway

MICHELLE LEWIS

Dominion Post 18/03/2013

An artist's impression of the planned Basin Reserve Flyover.

It and the board of inquiry that gave the green light to the expressway are wrong. There is no reason to believe four lanes from Levin to the airport will improve traffic in Wellington, or facilitate economic development.

To try to understand why this route is so important, I checked the Ministry of Transport statistics on freight movements. In 2006-2007 less than 0.004 per cent of all freight within New Zealand was moved by air. I concluded that it's not about getting freight to the airport.

So it must be about getting people to the airport.

According to Wellington Airport's audited annual report dated 31 March 2012 "domestic passenger numbers were flat". So no growth there either.

My next stop is New Zealand Transport Agency's traffic count data. It shows that for the 10-year period 2002-2012 traffic volumes on SH1 through Levin at Oxford St have fallen from 13,870 vehicles per day to 12,909 vehicles per day.

At Paraparaumu there were 24,300 vehicles per day in 2002 and 24,428 in 2012, an increase of 128 vehicles per day. Mackays Crossing has the biggest increase I could find, from 23,600 vehicles per day to 23,974 vehicles per day in 2012. That is an increase in traffic volumes of 1.5 per cent over the 10-year period.

Statistics NZ Commuting Patterns in New Zealand 1996-2006 showed that in the 2006 census 60 per cent of people living on the Kapiti Coast worked in the district.

This was the highest proportion of all the main centres in Wellington. It means the Kapiti transport network doesn't need to carry large numbers of people into Wellington for work. There is no new information available to suggest this has changed.

Put simply, there is no evidence to back up the constant messages that a four-lane expressway is needed for the future.

This is not to deny that some improvement will be necessary. The question is whether a high speed four-lane expressway is what is needed, or will even be helpful.

My own research has found that even NZTA officers believed the best option for such a road through Kapiti was along the existing SH1 and railway corridor. This was in line with NZTA's own urban design panel review of the options, a review that was discounted by the board of inquiry.

I spent 12 years working in Birmingham City Centre, known for the original spaghetti junction and its concrete collar, an elevated four-lane high speed road that circled the city.

For the past 20 years to enable economic growth and development, the city engineers have been demolishing the elevated motorway and reconstructing the boulevard-style roads they took away decades earlier in an effort to massage life back into the city.

It has worked - the removal of the elevated road network has brought major business and investment to the city.

When I saw the proposal put forward by Kapiti Coast District Council for the two-lane Western Link Road, I had no hesitation in backing the concept. It would be world class, 21st century infrastructure.

I am amazed that similar approaches are not being taken at the Basin Reserve. Birmingham is not alone, there are many cities around the world that are knocking down elevated motorways in urban areas and replacing them with boulevards.

Why isn't this modern approach being adopted in Wellington, especially when it will get better economic and social outcomes at lower cost?

The Mackays to Peka Peka board of inquiry was provided with results of tests that showed a two-lane local arterial would provide journey time-savings for all journeys, local, regional and national.

Little or no mention of such details are provided in the draft report.

Traffic engineers in the 1950s thought elevated motorways would solve congestion.

We now know building new roads provides no long-term congestion benefits.

The models that are being used in the Wellington area do not represent what will actually end up happening.

Michelle Lewis is an independent transport consultant who has previously worked in the UK, for the New Zealand Transport Agency, and for Kapiti District Council.

Saturday, March 16, 2013

Forecast: more traffic chaos ahead for Auckland

By Mathew Dearnaley

NZ Herald 9 March 2013

An accident which blocked all four of the Southern Motorway's southbound lanes forced major roads to back up throughout the city last week. Photo / Brett Phibbs

Although the city has struggled through its busiest traffic week of the year, culminating in Thursday's chaos after a serious crash closed all four southbound lanes of the main motorway out of town, Auckland Transport warns of a difficult weekend.

It is urging Aucklanders and their visitors to consider using public transport or share car rides with friends or neighbours as hundreds of thousands of people throng to a raft of events over the weekend.

Commuters stewed in traffic queues over three successive afternoons, but the longest were caused by the cascading impact of a 2-hour closure of Newmarket Viaduct's southbound carriageway at the height of Thursday's peak travel period.

The viaduct is the country's busiest section of motorway, normally carrying 7000 southbound vehicles an hour during afternoon peaks, and the closure from a serious crash could not have come at a worst time for what the Transport Agency acknowledges is a highly sensitive urban traffic network.

regional traffic operations manager Kathryn Musgrave told the Weekend Herald.

"This happened at 3.50pm, right smack in the peak, so it was during the worst time."

Not only that, but Auckland Transport says this was already the busiest traffic week of the year, as students hasten to the first classes of term joined other commuters trying to make an earnest start back at work from the summer holidays.

The phenomenon known as "March madness" happens every year, and tends to ease off after the first frenzied week, but Automobile Association traffic spokesman Phil Allen says he has never seen a worst example of gridlock than on Thursday afternoon.

"When you have your biggest traffic arterial flowing out of the centre of the city suddenly stopped, it's like a river," he said.

"You block a river and the water just keeps building up and up with a ripple effect coming back and back and it tries to ooze out into other tributaries and blocks up those.

"The whole network got constrained and blocked itself."

Ms Musgrave said recent major projects such as the Victoria Park motorway tunnel and the Newmarket Viaduct replacement had increased capacity in the network, and improved the reliability of journey times during most times of day.

But she said all big cities suffered congestion during peak periods, and there was no way to design a network of constantly free-flowing traffic without ending up with "20 lanes of motorway".

The best her organisation could do was to keep developing a range of travel choices for people by investing in projects such as rail electrification and busways, and improving lines of communication to give drivers early knowledge of unplanned incidents, so they could alter travel plans.

That would include a new service to be introduced before Easter in which drivers could subscribe to email alerts to their smart-phones.

By Mathew Dearnaley Email Mathew

Thursday, March 7, 2013

Fare free transit is spreading

How Free Transit Works in the United States

By Eric JaffeAtlantic Cities

Earlier this year the Estonian capital of Tallinn

became the largest city in the world — with a population exceeded

400,000 — to make its transit system free. (See reports about Tallinn elsewhere on this site. Ed). Tallinn marks the latest in a

growing trend toward fare-free transit on the Continent. The city is joining others to form the Free Public Transport European Network in an effort to spread the idea even farther.

It seems unlikely that American cities will take a cue from Tallinn, but those considering a fare-free system have a ready example in the United States: Chapel Hill. Since going fare-free back in 2002, Chapel Hill Transit has seen ridership increase from around 3 million passengers a year to just about 7 million. The system is now the second-largest in North Carolina and helped Chapel Hill win a City Livability Award back in 2009.

"It's not uncommon for us to get calls or emails from folks saying, How did you go fare-free?, and Can we make this work in our community?" says Brian Litchfield, interim director of Chapel Hill Transit. "I'm always careful to say this is a community decision. It's not something the agency or transit system can make necessarily by itself."

The agency considered shifting to a fare-free system back in 2001 after recognizing that its farebox recovery rate was quite low — in the neighborhood of 10 percent. Most of its revenue was already coming from the University of North Carolina, in Chapel Hill, in the form of pre-paid passes and fares for employees and students. To go fare-free, the agency just needed a commitment from a few partners to make up that farebox difference. The university agreed to contribute a bit more, as did the taxpayers of Chapel Hill and Carrboro, and the idea became a reality.

Today, says Litchfield, the agency's budget is around $19.5 million. According to a recent funding breakdown [PDF], U.N.C. puts up about 38 percent of that total, followed by 18 percent from Chapel Hill itself, with another 7 percent from Carrboro. State and federal assistance combines for 28 percent, with the remainder coming from small charges and fund transfers. The budget grows about 8 percent a year in wages, benefits, and fuel costs, says Litchfield, and the partners must find ways to increase their share by that much — and even more if they want service expansion.

"We look at it as a pre-paid fare program," he says. "The university is paying for all their employees and students to ride. The town of Chapel Hill and Carrboro are pre-paying their fares via property tax and vehicle registration fee. So while there's not a fare to get on the bus, it's definitely not a free system."

The original decision to go fare-free was part of a larger push by the community toward a transit-oriented lifestyle. In addition to eliminating bus fares, Chapel Hill Transit decided to expand service by about 20 percent. Meanwhile the university reduced parking on campus, Chapel Hill adjusted parking requirements in the downtown area, and the entire community made a push for denser development in the transit corridors. The ridership growth since 2002 can be seen as the result of all these efforts combined, says Litchfield.

"All of those kinds of went together," he says. "It wasn't just a decision — if we take fares away a bunch of people are going to ride."

Some of the benefits are obvious. Road congestion would be much worse, with many if not most of the 35,000 weekday trips provided by Chapel Hill Transit traveled instead by single-occupancy vehicle. Space devoted to parking has been reduced, as (presumably) have carbon emissions.

When speaking to detractors of the fare-free system, Litchfield likes to point out the measurable savings as well. The transit agency saves money that would be spent on fare collection, in terms of both staff and equipment (the system has 99 buses, and farebox devices sell in the area of $15,000 each). Advertising costs are down, since Chapel Hill Transit doesn't have to promote its pass programs, and the system also saves money that would have gone toward low-income ridership assistance. Last but not least, the buses save time because they no longer have to check passes or wait for fare swipes.

"When you tell folks that they go, Oh, ok," he says. "It makes a little bit more sense."

That's not to say going fare-free is necessarily the right move for all cities. Litchfield emphasizes four points to communities that approach him for advice. The first is obviously finding a committed funding partner. The second is that service quality must be maintained; if you take away fares but can only send a bus on a route every hour, that does no good.

The third challenge is funding para-transit service. Systems that provide fixed-route bus service must also provide para-transit service, but instead of being able to charge twice the normal fare, the fare-free financing structure must now cover these programs too. Last, you have to account for policing the system, with an emphasis on removing joy-riders.

"There's a very real cost for providing the service," Litchfield says. "But again, the benefits for that outweigh the cost of that in our minds and in the minds of our partners."

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

It seems unlikely that American cities will take a cue from Tallinn, but those considering a fare-free system have a ready example in the United States: Chapel Hill. Since going fare-free back in 2002, Chapel Hill Transit has seen ridership increase from around 3 million passengers a year to just about 7 million. The system is now the second-largest in North Carolina and helped Chapel Hill win a City Livability Award back in 2009.

"It's not uncommon for us to get calls or emails from folks saying, How did you go fare-free?, and Can we make this work in our community?" says Brian Litchfield, interim director of Chapel Hill Transit. "I'm always careful to say this is a community decision. It's not something the agency or transit system can make necessarily by itself."

The agency considered shifting to a fare-free system back in 2001 after recognizing that its farebox recovery rate was quite low — in the neighborhood of 10 percent. Most of its revenue was already coming from the University of North Carolina, in Chapel Hill, in the form of pre-paid passes and fares for employees and students. To go fare-free, the agency just needed a commitment from a few partners to make up that farebox difference. The university agreed to contribute a bit more, as did the taxpayers of Chapel Hill and Carrboro, and the idea became a reality.

Today, says Litchfield, the agency's budget is around $19.5 million. According to a recent funding breakdown [PDF], U.N.C. puts up about 38 percent of that total, followed by 18 percent from Chapel Hill itself, with another 7 percent from Carrboro. State and federal assistance combines for 28 percent, with the remainder coming from small charges and fund transfers. The budget grows about 8 percent a year in wages, benefits, and fuel costs, says Litchfield, and the partners must find ways to increase their share by that much — and even more if they want service expansion.

"We look at it as a pre-paid fare program," he says. "The university is paying for all their employees and students to ride. The town of Chapel Hill and Carrboro are pre-paying their fares via property tax and vehicle registration fee. So while there's not a fare to get on the bus, it's definitely not a free system."

The original decision to go fare-free was part of a larger push by the community toward a transit-oriented lifestyle. In addition to eliminating bus fares, Chapel Hill Transit decided to expand service by about 20 percent. Meanwhile the university reduced parking on campus, Chapel Hill adjusted parking requirements in the downtown area, and the entire community made a push for denser development in the transit corridors. The ridership growth since 2002 can be seen as the result of all these efforts combined, says Litchfield.

"All of those kinds of went together," he says. "It wasn't just a decision — if we take fares away a bunch of people are going to ride."

Some of the benefits are obvious. Road congestion would be much worse, with many if not most of the 35,000 weekday trips provided by Chapel Hill Transit traveled instead by single-occupancy vehicle. Space devoted to parking has been reduced, as (presumably) have carbon emissions.

When speaking to detractors of the fare-free system, Litchfield likes to point out the measurable savings as well. The transit agency saves money that would be spent on fare collection, in terms of both staff and equipment (the system has 99 buses, and farebox devices sell in the area of $15,000 each). Advertising costs are down, since Chapel Hill Transit doesn't have to promote its pass programs, and the system also saves money that would have gone toward low-income ridership assistance. Last but not least, the buses save time because they no longer have to check passes or wait for fare swipes.

"When you tell folks that they go, Oh, ok," he says. "It makes a little bit more sense."

That's not to say going fare-free is necessarily the right move for all cities. Litchfield emphasizes four points to communities that approach him for advice. The first is obviously finding a committed funding partner. The second is that service quality must be maintained; if you take away fares but can only send a bus on a route every hour, that does no good.

The third challenge is funding para-transit service. Systems that provide fixed-route bus service must also provide para-transit service, but instead of being able to charge twice the normal fare, the fare-free financing structure must now cover these programs too. Last, you have to account for policing the system, with an emphasis on removing joy-riders.

"There's a very real cost for providing the service," Litchfield says. "But again, the benefits for that outweigh the cost of that in our minds and in the minds of our partners."

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Friday, March 1, 2013

Free public transport for students & disabled in Riga

Riga is the capital and largest city in Latvia, in the Baltic States, with a population of nearly 700,000. Ed

RIGA - Riga City Council's Traffic and Transport Committee today approved free public transportation for vocational school students and persons with third category disabilities from March 20 this year, Riga City Council informed LETA.

The original proposal was to introduce free public transport for persons with third category disabilities from March 15 and for vocational school students from September 1. However, the committee's chairman Vadims Baranniks (Harmony Center) proposed that the discounts commence already on March 20, and the committee approved his proposal.

From the Baltic Times. Feb 2013

RIGA - Riga City Council's Traffic and Transport Committee today approved free public transportation for vocational school students and persons with third category disabilities from March 20 this year, Riga City Council informed LETA.

The original proposal was to introduce free public transport for persons with third category disabilities from March 15 and for vocational school students from September 1. However, the committee's chairman Vadims Baranniks (Harmony Center) proposed that the discounts commence already on March 20, and the committee approved his proposal.

From the Baltic Times. Feb 2013

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Send

Send